Rick Cross transitioned from war to civilian life via public service

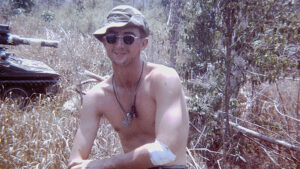

Airborne Ranger

CHARLOTTE — In the late 1960s, the military was taking 5,000 men per month in Minnesota alone. It was the height of the Vietnam War.

Rick Cross is 74 these days, and back then, at 18, he graduated from Osseo High School. It was 1967. After, he attended the University of Minnesota part-time and worked a factory job a couple of years. The draft was a regular part of life. Young men awaited their notices in the mailbox.

“We all knew we were going. It was just a matter of when and where,” Cross said.

In 1969, he signed up to be a Navy medic with a classmate on the buddy program. They passed the physical test, but his buddy couldn’t pass the written test to be a medic.

So much for joining.

Two weeks later, the Army drafted him and used the Navy tests.

Cross wanted to be a mechanic, but that required an extra year, so he ended up an 11B infantryman.

Basic was at Fort Bragg, N.C. During the second week of basic, the base commander, a one-star general, summoned Cross. None of the brass or drill sergeants knew why.

Cross walked in, saluted and reported. The brigadier general, it turned out, was a cousin. Cross’ mom had called the general to find out how her son was doing.

“The drill sergeant found out I was related to the base commander. I pulled KP throughout basic,” Cross said.

After advanced infantry training at Fort McClellan, Ala., Cross finally got to go home and see his mother. He said: “Please don’t do that again.”

The men were being fast-tracked into regular duty. Basic was six weeks. AIT six weeks. Cross agreed to attend Airborne school and Ranger school.

“Recruiters said, ‘If you are not Airborne, then you are not nothing.’”

Jump school was three weeks; Ranger four. He had two weeks off, then it was off to Vietnam. There, he spent a week at Snake School, where soldiers are taught to survive in jungle. Then he was sent to the HQ of the 2nd Battalion, 16th Infantry Regiment “Rangers.” HQ was assigned to B Company. In Vietnam, the 16th served with the 1st Infantry Division — the Big Red One.

His platoon, always short on personnel, would go out on patrols for 30 or 40 days at a time. They had worked the well-known Michelin rubber plantation. At Firebase Keene, they faced a ground attack. During these patrols, the men grew beards, and some had Mohawks. All had rotten uniforms.

Being new, he didn’t know what was going on.

“When I got there, they still had K rations. Then they got C Rations,” Cross said.

They would be in firefights, and little kids behind them would pick up brass casings. People were dying, and the children were used to it. Most of the enemies they faced were Viet Cong.

One time, his platoon crossed the Ho Chi Minh Trail, and they set up an ambush. They even would see people riding bicycles while carrying weapons.

While on patrol, the company commander radioed there was a Navy base five miles away. They walked there and went to the mess hall.

“We reeked,” Cross said. “We had beards and had no showers for three weeks.”

A young Marine in a starched uniform would not let them in. Why?

“Just look at you.”

Cross walked to his gunner and instructed him to point his firearm at the Marine but not shoot him. He did. The Marine was scared. Meanwhile, a sailor saw the scene and scrammed.

The soldiers were fed. They relieved the gunner, who ate, and they left. The Marine guard then reported the incident to the Officer of the Day, who put the men in the brig.

There, they lived the high life. They enjoyed showers, shaves, clean clothes and a comfy jail bed.

“We were enjoying it, basically,” Cross said.

About a day and a half later, the Navy captain came in one day and said they were free to go. Cross inquired why.

The captain replied: “I got some irate Ranger call me and say, ‘Let those lazy sonovabitches out of jail so they can complete their mission.’”

Ever heard of the Rung Sat Swap? The patrols would set up ambushes there. Water would be one to five feet deep or so. The land crabs would dig holes or crawl on the soldiers at night, Cross said. They would crawl right on the face but not hurt the human.

Leeches, however, were six to eight inches long and would attach all over. Soldiers would burn them off with cigarettes.

“Between the leeches, the scorpions and the giant ants, it was weird,” Cross said.

His first tour was 11 months. The 16th Regiment, along with the entire 1st Division, all went back to Fort Riley, Kan., where they were based. Because Cross had not been in Nam for a year, he got pulled out and sent to be part of the 25th Infantry Division — “Tropic Lightning” — with the then-unmentionable task of going into Cambodia.

It wouldn’t be his first time there. One time, on patrol in the 1st Infantry Division, they went into Cambodia in uniforms with no names, country, flag or unit designations. They didn’t exist. They weren’t there.

During that patrol, they got ran out by the North Vietnamese Army, much more experienced than the VC. The Americans had to perform a Claymore extraction. They would hit the NVA with Claymore mines, then run like hell for the helicopter.

Once Cross reached a year in Vietnam, he decided to extend a year. There was an economic recession back in the States, and the country was in turmoil over the war. He figured there were no jobs, particularly for undesired veterans.

With the 25th, he was part of the 1st Battalion 27th Infantry, aka “Wolfhounds.” He was an M-60 gunner, and, upon landing on a hot LZ in Cambodia, Cross, bearing a heavy pack, fell, perhaps on a stick or tree root, he said. A big Texas assistant gunner pulled him up easily with one hand.

They ran to attack an NVA base camp after Air Force bombers had swept it. There were dead enemies with their body parts all blown up. The soldiers of the 25th closed out any remaining enemies.

Next, the brass set the team up in a town for three days, and they patrolled the area known as the Parrot’s Beak — a portion of Cambodia that protrudes into Vietnam. There were NVA all over. Cross was an E-5 buck sergeant by now.

He was skinny, too, and the skinny guys did the duty of tunnel rat. He did it three times with the Wolfhounds, and, after that, he said he was done. No more.

Two guys would crawl in with a .45 (officially the M1911A1 Service Pistol) and a flashlight. Two of those times, it was uneventful. They would crawl out and toss a grenade inside to collapse the tunnel.

One of the times, he got 25 feet down, and he heard voices. People were talking. He motioned to the second guy to prepare the white phosphorus grenades.

“We chucked a couple of Willie Peters down there, and we could hear them screaming,” Cross said.

On patrol one day, they found an NVA rice cache. They waited, and at night, took out an NVA soldier who visited the cache.

A couple of nights later, their patrol of six got hit by the NVA.

Cross and the medic were in a foxhole dug by the rice cache. Meanwhile, the team leader was shot and killed trying to outrun a bullet.

“We thought, ‘We’d better move,’ and as soon as we did, the bullets began striking the ground by where our feet were,” he said.

The machine gunner opened up, ending the NVA attack.

Another night, there was a point when, at 11 p.m., a father and son came to the rice cache with two ox carts. Curfew was 10 a.m. The two men were restocking the cache. The U.S. soldiers took them out.

The colonel and battalion commander came out and told the patrol what a fine job they did. They left and sent a chopper to pick them up and bring them to the rear. They learned the South Vietnamese government wanted to file charges against them. One of the men on the road was a religious leader. If convicted, they could go to LBJ, a presidential nickname for a Saigon prison actually named Long Binh Jail.

They waited a week, and during this time he got in trouble for stealing the judge advocate’s Coca-Cola. (If you see Cross in person, ask him about stealing this soda.)

Finally, they got to ride out with the battalion commander to the site of the killing of the religious official and showed how the religious man was out after curfew and bringing rice to the cache. The person was an NVA sympathizer and an enemy of South Vietnam.

Cross and his men were released.

The war took a new direction — Vietnamization — and the Army was offering early-outs. Cross took it and returned to Minnesota. His wife, Linda, was pregnant. She gave birth to a boy.

He had considered working a mercenary job in Africa, where he would train officers (which was legal then), but his wife didn’t want him returning to combat. He had to get a job.

He decided to re-enter the Army, and he served another 28 years, the final three with the Army Reserves.

He finished as a senior non-commissioned officer. Though he retired as a 1st sergeant, he did achieve the rank of command sergeant major during a unit drawdown.

The career path took him to Japan, Congo, Thailand, Fort Benning, Fort Bragg again and Fort Hood. His Reserve duty was at Fort Snelling.

He also served a year with a Ranger unit in the 172nd Infantry Regiment in Alaska. He learned to leave his motor vehicle running 24 hours a day, and if he didn’t cover his hands at night when taking an outdoor leak, it could lead to frostbite. One time, they stole fish from bears near a river and brought them to the chow hall to cook. The meal was excellent.

He got out in 1995 and worked at a factory. The company was purchased, and the new company offered a 30-year pension to anyone who quit. Cross resigned within 30 minutes.

Meanwhile, Linda worked at US Bank headquarters as a data analyst. Together, they built a house on Big Sauk Lake. They moved there in 2003 and got active in The American Legion with Sauk Centre Post 67.

It all started when he asked for a good place to icefish. In that spot, he caught a single crappie. He brought it to share with a group of guys nearby, and they had bunches of crappie. He got to know those guys in the Legion, and they soon nominated him for a district committee chairman role. He continued on to be district commander and now has a national appointment. He says he is on his way down now and wants young veterans to move up.

“Let the young guys do this stuff. Let’s mentor the younger guys,” he said.

He has been a Legionnaire for 39 years. About 10 years ago, he moved his membership to Melrose Post 101, where he is today. Public service is important to him. He also is a member of the SAL and Riders.

Linda died of cancer in 2020. They had been married for 51 years. His mother died the same year.

Cross and Sharon Thiemecke had known each other for 20 years.

“I got lonely and started dating her,” he said. “She’s the smart one of the two of us.”

He explained that they found one another to be comfortable.

They got married Memorial Day 2023. They are now Rick and Sharon Cross. She is a member of Bemidji Unit 14 and the president of the American Legion Auxiliary Department of Minnesota.

He brings his son, now a 52-year-old engineer. She brings five grown children, two girls, two boys.

You see them at Legion Family events, whether at the 104th National Convention in Charlotte or the Camporee up at Legionville or the State Bowling Tournament in Dayton.

They are nearly inseparable. When they are separated, it is usually because she has a business meeting, or a presidential duty, and there he is, waiting patiently outside the door to drive her home.