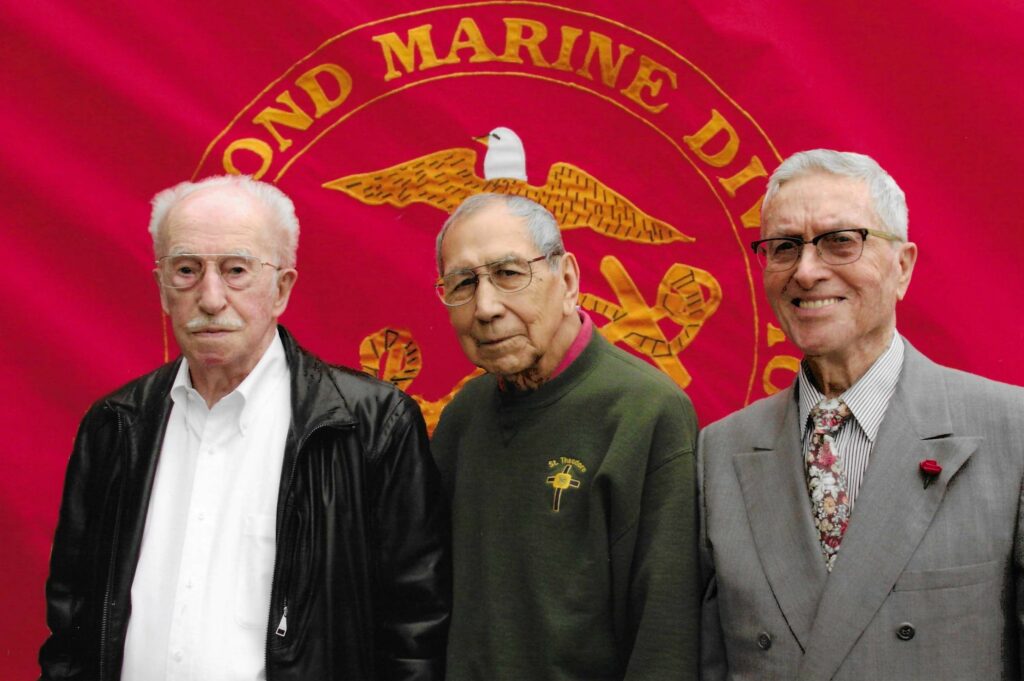

One of the final Tarawa veterans recalls battle from 80 years ago

ALBERT LEA — On a hot November day 80 years ago, 21-year-old Pfc. Lupe Gasca found himself on the other side of the world, wading through a chest deep lagoon with Japanese bullets hitting the water to his left and right. Now 101 years old, the lifelong resident of Albert Lea recalls his involvement in one of the defining battles of World War II — the Battle of Tarawa.

Gasca was born in Texas, but moved to Albert Lea in May 1922, when he was just 2 months old. His parents were farmers, moving to town to obtain work harvesting sugarbeets. They stayed and continued on in the town as tenant farmers. Gasca’s young life was characterized by hard work — he grew up during the depression, worked as a farmhand and went to school on a part-time basis. But he always loved to visit the library and was particularly interested in its collection of images from the First World War.

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Gasca was working part-time as a store clerk. He knew his name would be called in the draft, and remembering the images of trench warfare from the library, made a choice.

“I said, ‘Well, I’m not going to join the Army,” Gasca recalled. “I’m going to go in the Marine Corps, because I’ll get the easy job. I’m not going to be crawling in the mud like those guys.’”

And so, he joined the Marines.

When Gasca went overseas, he was first sent to New Zealand. There, he joined his unit, 1st Battalion, 2nd Marine Regiment. The regiment was resting and refitting after participating in fighting at Guadalcanal, the first major American ground offensive in the Second World War. The United States had prevailed against the Japanese at Guadalcanal, halting their imperial ambitions, protecting Australia, and taking the first step in a long journey of “island hopping” across the Pacific. When Gasca arrived, he was assigned to a machine gun team in B Company, under the command of Capt. Maxie Williams. The Marines of B Company were preparing for the next offensive, a landing on a small island called Betio.

Betio is an island in Tarawa Atoll, located in the Gilbert Islands of the Central Pacific Ocean. Though just over two miles long, and 800 yards across at its widest, Betio was home to a runway from which Japanese aircraft could delay the American advance toward Japan. Despite its size, and sitting just ten feet above sea-level at its highest, the Japanese had intensely fortified Betio.

They had constructed concrete-reinforced fighting positions and command posts, and surrounded the island with a log seawall, complemented in places with barbed wire and mines. Garrisoned there were 2,600 Japanese naval infantry, considered Japan’s first-rate troops. The island also had a natural wall, a barrier reef surrounding it. At low tide, the reef was insurmountable to conventional landing craft, rendering an amphibious invasion difficult, if not impossible. Reflecting on Tarawa’s defenses as the invasion loomed, the garrison’s commander, Rear Admiral Meichi Shibasaki said, “A million Americans couldn’t take Tarawa in 100 years.”

After rehearsing the landings, the Marines of the 2nd Marine Regiment, along with the rest of the 2nd Marine Division, set sail for Tarawa. Gasca’s 1st Battalion was assigned to be the regimental reserve, meaning they would land following the 2nd Regiment’s other battalions. Even so, at about 2 a.m. on Nov. 20, 1943, Gasca and the other Marines of the 1st Battalion shuffled into the ship’s galley for their pre-invasion meal. After breakfast, they climbed down cargo nets strung over the sides of the transport ships, and into landing craft idling in the water below.

“It was just pitch dark as could be,” Gasca remembered. “I could see the shadows of the other ships, and some Higgins boats already making their circles. And just as I got down on the Higgins boat, I heard this funny whistling noise, right over the top of us. It was a shell! I’d never heard anything like that.”

The sun rose, and the Marines in the landing craft continued to wait to head for shore. To surmount the island’s barrier reef, a very limited number of new amphibious tractors, called “amtracs” had been procured. These tracked amphibious vehicles were able to crawl over obstacles that might have stopped traditional landing boats. But precious few were available. So a system was devised where the amtracs would make a shuttle service, ferrying waiting Marines from the landing boats to shore. However, the system didn’t work as smoothly as had been hoped.

“They said, ‘They’re landing, and they’re going to come back,’ and so we were waiting for that 15 minutes it was supposed to take.” Gasca said. “It was hours before I finally got there.”

However, Gasca didn’t need to wait hours to be introduced to the harsh realities of war.

“To my left — and I could almost see the shell!” he remembered. “Their coxswain was hit and just disappeared.” He watched helplessly as the Marines in that landing craft were thrown about, becoming casualties before even reaching the island. When the amtracs arrived to shuttle Marines in, there wasn’t room aboard for Gasca and his gunner, Alfred Lewis, so they continued to wait in their landing craft. Finally, a lieutenant aboard their boat ordered the coxswain to take them ashore. They weren’t quite there when the landing craft ground to a halt, scraping bottom on the reef.

“And then, the ramp went down.” Gasca recalled. “We were still about 200, maybe 300 yards from the beach. And we were very lucky that when the ramp went down and we started walking, the water was only up to here.” Gasca said as he drew a line with his hand in the middle of his chest.

“There were no holes. But what happened to some other people — tanks completely, even — the ramp went down, and the unit went down. The sailors dropping us off were just as green as we were, they didn’t know.”

Gasca began the long walk in to shore, with Japanese bullets hitting sporadically all around him.

“At that time, I’m just hoping I don’t get hit,” he said. “When I got off of the Higgins boat into the water, there was no reason to be scared because there was nowhere to go but forward. Lewis and I weren’t even talking, we operated just on instinct.”

Having made it to shore, he and his gunner recognized nobody. The Marines they encountered were from a different unit — the landing was completely confused. Many landing craft did the same as Gasca’s, dropping Marines off on the reef to walk ashore rather than waiting for amtracs. And then came the trouble of logistics — supplies were missing, communications were inoperative, and the Marines had encountered fiercer resistance than expected. As a result, the first waves didn’t move inland, and the following waves had piled up on the beach behind them.

“There was a bunch of debris, and I could see to the left the big bunker. I couldn’t see any of the enemy. They were underneath this debris and tin, and they could see us, and they were close,” he recalled. “There must have been buildings there, because there were tin roofs on the ground, with coconut trees fallen over on top of them. It was just like being in a pile of junk. And we just kept firing at the tin.”

Having joined a platoon of Marines fighting from Red Beach 2, Gasca and Lewis spent that first night on Betio stuck on the beach just yards from the water, and in the midst of many dead and wounded Marines.

One the second day, the two Marines were able to rejoin B Company. They spent the rest of that day and the next partnered with Marine riflemen assaulting the incredibly well fortified and concealed Japanese fighting positions. The fighting was exhausting, both physically and mentally. Danger was ever present, and hard to see coming. Once the enemy combatants had been located, it was a substantial effort to neutralize them. Often, Japanese positions were thought secured, only to present an active threat again later in the day.

On the night of Nov. 22, the third night of the battle, Gasca was dug in on the south side of Betio Island. He and Lewis’ machine gun was pointed towards the water, to stop any enemy who might try to swim out and infiltrate from the sea. Gasca was on watch, when he noticed movement on a Japanese position.

“At about 11 o’clock, I thought I saw some movement at this bunker. Now before it got dark, I hadn’t seen any door there. But pretty soon, I saw a couple of other guys moving. I had a rifle right next to my machine gun, and I picked up the rifle and I fired. And I hit him,” Gasca recalled. “Just as I fired, on top of the bunker — which was high and covered in sand and debris — about 20 guys came over the top! They were firing at us, and I spun my machine gun around and opened up. I didn’t even fire a belt, I probably only fired about 15 seconds. All the other guys opened up with rifles and BARs and everything,” he remembered. “And about the same time that I was doing this, a hand grenade landed to my left and killed some of the guys, and that’s when I got hit. I felt warm from my legs, and tried to move, and I fell down. So that’s when I got wounded. I’ll never forget that.”

For this action, Gasca received a Commendation with Ribbon. His citation notes:

“Serving as a machine gunner during a heavy enemy counterattack on Tarawa, although wounded, he maintained a continuous and accurate rate of fire upon the hostile forces until the counterattacking element was repulsed. His aggressive spirit and determination in this instance were typical of his conduct throughout.”

Lupe Gasca draws out a map of his path across Tarawa, while speaking to a reporter in his home last year.

Gasca was evacuated from Tarawa, and sent to a hospital in Honolulu. He recovered in time to join B Company in the rest of its campaigns in the Pacific, surviving the fighting on Saipan, Tinian and Okinawa. He served in the postwar occupation of Japan, witnessing firsthand the devastation wrought by the atomic bomb in Nagasaki, before returning home to Albert Lea.

The Battle of Tarawa is one that remains legendary in Marine Corps history. Of the notoriously vicious campaigns in the Pacific, Tarawa is remembered as one of the most brutal. In just 72 hours, there were over 3,000 American casualties on the island a little over a half-square mile in size. The Japanese had 4,690 men killed — only 17 soldiers and 129 of the Korean laborers brought to Betio by the Japanese survived. Casualty reports and images from the battle, particularly those shown in the 1944 Oscar-winning documentary “With the Marines at Tarawa,” shocked the American public.

The battle though, was important. Admiral Chester Nimitz, commander of Allied Forces in the Pacific said, it “knocked down the front door to Japanese defenses in the Central Pacific,” and it influenced American doctrine in amphibious operations to come.

For the first time, Americans encountered a deeply entrenched enemy in the Pacific — a strategy used by the Japanese throughout the rest of the war, and made famous in places like Peleliu, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. Eighty years on, remnants of the battle are abundant on Betio, and efforts continue to recover the remains of Marines still buried in lost graves on the atoll, among them Arthur Wende, who was killed leading Gasca and Alfred Lewis to a fighting position.

Though 80 years have passed since his first combat experience at Tarawa, the scene remains etched in Lupe Gasca’s mind.

“I remembered two things I forgot to mention last time we talked,” Gasca said to me one afternoon in his living room. “The heat and the smell. The smell of death … I can still smell it right now. I’ll never forget that.”

But even so, Gasca’s participation in the event doesn’t loom large in his mind. He doesn’t see himself as a hero. “It’s a long time ago, and you know, over the years I never talked about it. I came home and got married and raised a family, and we never talked about it. In fact, even when I got back to B Company right after the battle, we never talked about it,” Gasca said. “But after so many years, I wondered — why did they do it like that?”

Gasca is one of the very last who remember firsthand the fighting for bloody Tarawa. He is a 59-year member of Albert Lea Post 56. He turns 102 on March 12.

Be sure to send him a birthday card. Mail to Lupe Gasca, 1009 Fairlane Terrace, Albert Lea, MN 56007-3557.