Meet Minnesota’s PTSD doctor

Not just anyone can have PTSD; there must be certain stressors

APPLE VALLEY — Rarely mentioned by historians is that Socrates was an 11 Bravo.

The great founder of Western philosophy served as a hoplite in the Athenian army in the Peloponnesian War — at the siege of Potidaea in 432 BC, assault on Delium in 424 BC and the defense of Amphipolis BC in 422 BC. Hoplites were foot soldiers armed with spears and shields, commonly fighting in close formation. They were the infantry.

When he came home, Socrates walked the streets asking questions, noted Steve Lansing, a Rochester-based psychologist with Empower Treatment Center and a Vietnam veteran. He is a member of Minnesota Post 1982, the at-large post.

A man likely experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder questioned the world around him — and eventually attracted youthful followers eager for his knowledge. This led to what today is called the Socratic Method, a means of learning where the teacher asks probing questions to explore a student’s views and opinions. Ironically, Socratic dialogue can serve as cognitive therapy for PTSD.

Lansing gives a compelling presentation on PTSD. He gave one at the 3rd District Mid-Winter Conference in Apple Valley.

Lansing said he struggled with college and joined the Air Force. He spent two years in Vietnam with the 7th Air Force doing intelligence analysis.

On the domestic flight home, a flight attendant dumped a drink on him after learning he served in Vietnam. She called him a “baby killer.”

After, Lansing decided to go back to college, finished in three years, then went to grad school. In 1986, he moved to Rochester from Iowa to run a suicide hotline. He found one in three of the callers were veterans. He learned that many Vietnam veterans were dealing with untreated PTSD.

“Seventy percent of the people in prison in the 1970s were Vietnam vets,” he said.

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington was dedicated in 1982, and in 1984, Lansing attended a conference in the nation’s capital. He visited the wall, and a man said, “What’s that ugly thing?”

Lansing replied, “The good thing is my name is not on that wall.”

The stranger said he didn’t realize the wall was dedicated to the Vietnam veterans.

One day, Lansing was at a bar. A man kicked a pop can, and Lansing dived on it. He said people with PTSD live in a parallel universe, with possible triggers all around, from thunderstorms to the silence of night.

“We are aliens on a strange planet,” he said.

It’s why veterans back into parking places and don’t sit with their back to the door.

Lansing spoke against Hollywood celebrities and other civilians who claim PTSD over the slightest of grievances, watering down the seriousness of the term.

He added there have been famous actors who indeed struggled with PTSD: Audie Murphy and Jimmy Stewart are among them.

PTSD, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM-5-TR (i.e.: fifth edition, TR is “text revision”), requires one or more stressors. Not just any stressor, like a divorce or a job loss, but much worse stressors.

“PTSD is the only event-related mental disorder,” Lansing said.

The stressor is being exposed to one or more events that involved death, threatened death or actual injury or threatened serious injury or sexual violation — and in one of the following ways:

• Directly experiencing the event.

• Witnessing the event as it occurred to someone else.

• Learning a close relative or friend experienced the event.

• Experiencing repeated exposure to distressing details of an event.

The results are intrusive thoughts, avoidance, exclusion, negative cognition and moods, depersonalization, derealization, and alterations in arousal and reactivity.

Common examples are nightmares, guilt, poor judgment, loss of motivation, flashbacks, anxiety, lack of feelings, negative self-image, helplessness, depression, apathy, stress, irritability, anger, rage, frustration, communication problems, short-term memory, poor concentration, startle reflex and intrusive memories.

Civilians may ask: So you were shot at. So you saw dead bodies. So you witnessed dismemberment. What’s the big deal?

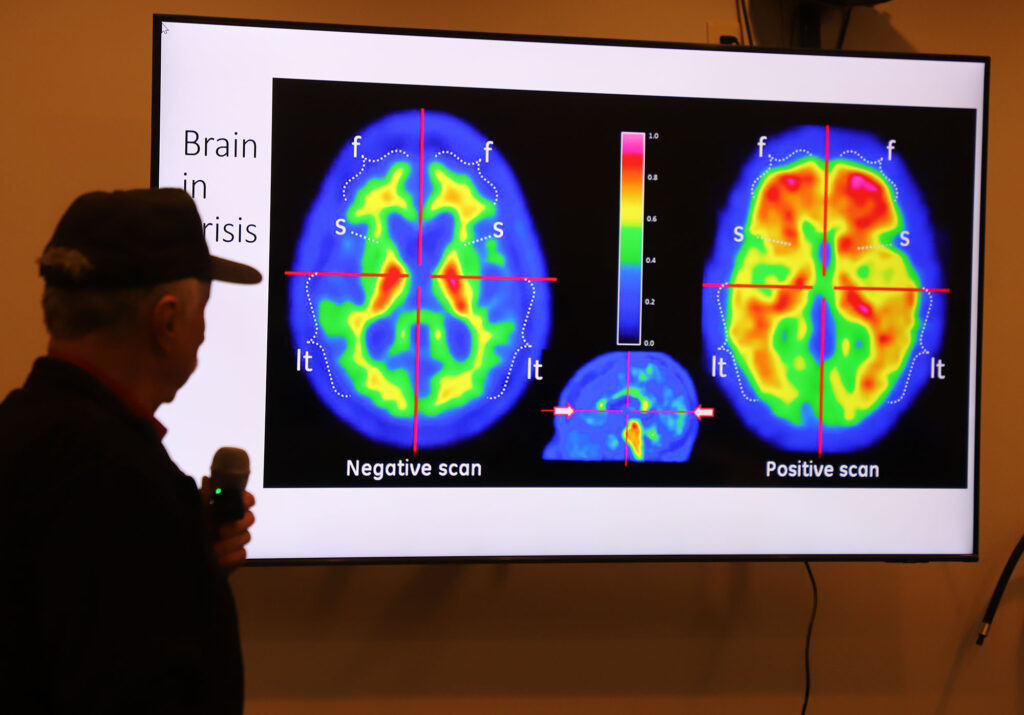

There are three parts of the brain, Lansing said, and whether veterans who experienced trauma like it or not, the PTSD affects all three parts. The hippocampus shrinks. The prefrontal cortex shrinks. The amygdala grows.

The doctor said hippocampus transfers and stores information into memories. A mind with PTSD stores memories incorrectly and retrieves them incorrectly.

The prefrontal cortex covers complex thinking and decision making. PTSD causes a dysfunctional thought process and leads to inappropriate responses to some situations.

The amygdala helps process emotions and is linked to fear responses. With PTSD, it sets that “fight or flight” in response to memories or thoughts about danger.

Lansing shared scans of brains: one healthy, one dealing with PTSD. The PTSD brain showed a busier prefrontal cortex.

“This is a brain working harder and harder than a brain is supposed to do,” he said.

The bad news? There is no off switch, he said.

The good news is being in the right environments and getting the proper therapy can help. He said people with PTSD are 10 times more likely to relapse than people struggling with drugs or alcohol.

“The legal system historically has not understood trauma cases, and it screws veterans who are in the court system,” Lansing said.

He added that veterans courts have been a good step in the right direction. He has taught PTSD to veterans courts.

Veterans also face PTSD from moral injuries caused by stressful circumstances. When someone does something that goes against their beliefs, this is an act of commission. When they fail to do something in line with their beliefs, it is an act of omission.

Lansing used examples. One was an officer ordering a bomb raid that stopped the threat but killed hundreds of civilians. Another was a soldier at Normandy who feels bad about surviving and guilty about killing the enemy because “those men had families, too.”

There are three things people can give veterans, and they can give each other, Lansing said:

1. Understand. “Never ask a vet if you killed anybody.”

2. Empathy. “I appreciate what you did. Thank you for serving.”

3. Support. “What can I do to help?”

Sharing the stage with Lansing and introducing him was ret. Col. B. Wayne Quist, a Legion member with Red Wing Post 54. Quist and Lansing have authored a book about PTSD in veterans called “Veterans in Crisis.” The book shares the long and ancient history of veterans dealing with trauma, including the tale of warrior philosopher Socrates.

by Dr. Steve Lansing

& Col. B. Wayne Quist

There is a memorable quotation from Athenian Gen. Thucydides, who had quoted the Spartan king: “The nation that makes a great distinction between its scholars and its warriors will have its thinking done by cowards and its fighting done by fools.”

And the book discusses current wars such as Ukraine and Gaza, and it discusses the growing destructiveness of combat, including nuclear armageddon.

The book states, “The U.S. Army concluded during World War II that almost every soldier, if he escaped death or wounds, would break down after 200 to 240 combat days. Breakdown was inevitable; about one-sixth of casualties were psychiatric, but most combat troops did not survive long enough to go to pieces psychologically. The pattern of ‘combat fatigue’ was universal on all fronts.”

“Veterans in Crisis” is found at vetsempowered.org and on Amazon for $17.95 starting May 7. Pre-orders are allowed.

If you are a veteran struggling with mental health, find a Vet Center near you for free, off-the-medical-record counseling. Minnesota has Vet Centers in Anoka, Duluth and St. Paul.

Veterans with PTSD often come in multiples

Dr. Steve Lansing shared a slide from a RAND survey that said 50 percent of veterans with PTSD report experiencing multiple traumatic events.

• Having a friend who was killed or seriously wounded: 49.6%

• Seeing a dead or seriously injured noncombatant: 45.2%

• Witnessing an accident with serious injury or death: 45%

• Smelling decomposing bodies: 37%

• Physically moved or knocked over by explosion: 22.9%

• Injured without hospitalization: 22.8%

• Blow to the head from accident or injury: 18.1%

• Injured with hospitalization: 10.7%

• Engaging in hand-to-hand combat: 9.5%

• Being responsible for the death of a civilian: 5.2%

PTSD before it was PTSD

By Dr. Steven Lansing

How the language has changed over the years:

• Civil War: Nostalgia, soldier’s heart, railway spine

• WWI: Shell shock, war neurosis

• WWII: Combat fatigue, combat stress reaction, flack happy

• DSM-I (1952): Gross stress

• DSM-II (1968): Adjustment reaction to adult life

• DSM-III (1980): PTSD coined, multiaxial, multipopulation

• DSM-IV (2000): Defined as direct exposure to extreme trauma, modern character symptoms established as anxiety disorder

• DSM-5 (2013): No longer an anxiety disorder; now trauma- and stressor-related disorders

• DSM-5-TR (2022): No major changes; narrowed Criterion A (stressor) slightly