John Kriesel: ‘Life is good, even when we think it is not’

ST. CLOUD ─ John Kriesel joined the Minnesota National Guard on his 17th birthday after watching U.S. forces on TV in the Persian Gulf War ─ not just a stint but as a career.

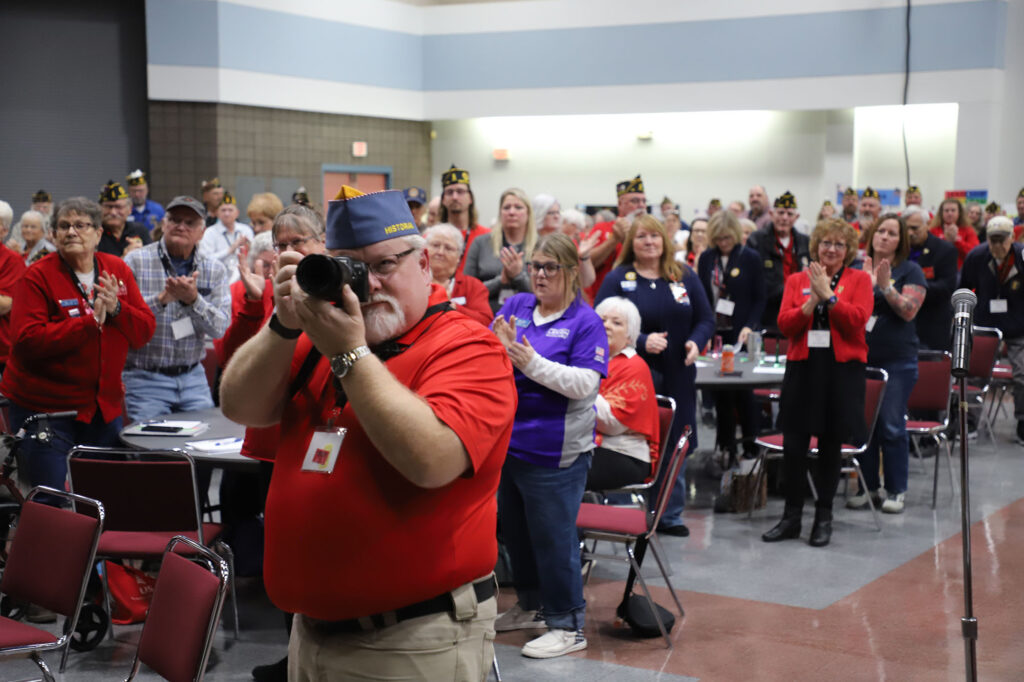

Kriesel spoke Oct. 24 during the American Legion Fall Conference at the River’s Edge Convention Center. Attendance at the Fall Conference was solid. The Convention Committee reported 451 registered attendees. Add in invited guests, paying exhibitors and a handful of folks who sneak in without paying, and it was above 500.

“This conference had a great speaker in John Kriesel, and we offered a lot of training that was focused on the mission of The American Legion,” said Chairman Tom Fernlund.

Kriesel said he had been quite the troublemaker until basic training after his junior year at White Bear Lake High School. However, he was well-behaved his senior year.

“Those drill sergeants were quite good at getting the smart-aleck out of me,” he told the Legion Family members.

When the military was deploying to the Mideast after 9/11, his unit was sent as a NATO peacekeeping force in Kosovo in February 2004.

“It was the first time realizing just how fortunate we are to live in the United States of America,” Kriesel said.

The chow hall showed news from wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and members of his unit felt like they were missing out on the Super Bowl.

By the end of 2004, Kriesel wanted to get out of the military and become an EMT with the Inver Grove Heights Fire Department. He got a call from a buddy three days out, a sergeant first class, who asked, “You’re not getting out, are you? There is a deployment to Iraq next year. Would you regret not going on the deployment?”

Kriesel reenlisted, and he ended up being part of what became known as the Long Deployment. The 34th Infantry Division’s 1st Brigade Combat Team had the longest continuous deployment of any unit during Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Of course, Kriesel, ever funny, points to his prosthetic legs and jokes that his deployment was shortened.

The Red Bulls spent five months training at Camp Shelby, Miss., followed by a month at Fort Polk, La. They flew to Kuwait and spent two weeks before ending up at a Marine Corps base called Camp Fallujah in Iraq.

There, they stayed in white tents and spent time learning the ropes from the unit they were replacing. Their job as to work the towers overlooking the camp and to perform patrols to push the enemy farther out. They found out a tent kitty-corner from them took a hit from a mortar round two or three days before.

They learned what it was like to wake up at 2 a.m. to the sound of artillery fire. They saw rockets fire every evening. They witnessed vehicles get lit up. The wanted the enemy farther away so they couldn’t make such attacks. Their patrols eventually pushed enemies farther and farther out, all the way past the Euphrates River.

The U.S. force at Camp Fallujah melded into a blended one of various units from the Army and Marines. Staff Sgt. Kriesel was in charge of six soldiers and three Marines. The entire force reported to a Marine colonel.

On Dec. 2, 2006, they were watching an intersection that was important because it was big enough for Bradleys. It was common to call OID to send a robot and clear bombs at that junction.

“Everyone knew that was a chokepoint,” Kriesel said.

Insurgents in Iraq weren’t necessarily Iraqis. They were people from other countries who wanted to fight Americans. This night, Kriesel and four others were pulled off that watch and sent in a Hum-Vee to patrol behind a Bradley. Kriesel sat shotgun, where he could operate the radio and talk to HQ.

They drove past checkpoints. They heard via the radio someone was spotted at Checkpoint 3-4 digging in the road. The trucks cleared CP 3-1 and CP 3-2. At CP 3-3, the soldiers in the Hum-Vee heard a faint “plink,” then this large wooshing sound, then the noise of sand and rocks falling to the ground and rocks hitting metal.

Kriesel opened his eyes. The Hum-Vee had been upended. It turned out the left, front wheel drove over a pressure plate that detonated 200 pounds of explosive.

“I felt very warm, very itchy. No pain. I was in shock,” Kriesel said.

He tried to lift himself and noticed it was harder than it should be. He looked down and saw his left leg was connected by the skin and his right leg was bleeding and looked like it had been in a wood-chipper.

“I was certain my life was going to end,” Kriesel said.

The Bradley stopped 125 meters ahead. They thought they had struck the bomb until they looked back and saw the Hum-Vee. Others called in a medevac helicopter, provided first aid and secured the site with the Bradley.

Kriesel describes how people in his unit spoke with him. Some sugarcoated his condition. Others were blunt. They also fought to keep him awake, literally.

Finally, they told him they had to move. You know it’s not a good day when they flip your legs onto your chest, grab you by the butt and move you.

He started to feel cold. He said prayers, but he didn’t want his family to hear that he suffered, so he got tough.

He told a sergeant major, “Tell my family I love them.” The sergeant major replied, “Shut up. You’re going to tell them yourself.”

A Marine CH-46 chopper transported them while a Marine Super Cobra chopper provided security. Eight days later, Kriesel woke up at Walter Reed Medical Center outside of Washington.

“Those doctors did not give up on me,” Kriesel said.

He learned his family had flown to Landstuhl, Germany, to see him. He was in a coma and woke up in D.C. to hear a soothing voice asking him questions.

Being an optimist, he said, is the way to live.

“I now can stretch out on love seats,” he said.

The staff at Reed helped him with PTSD so that his suffering today is primarily the result of being a lifelong Minnesota Vikings fan.

“Great men and women work at Reed,” said Kriesel, who today is 44, lives in Cottage Grove and is a Legion member with St. Paul Park Post 98.

Two men were killed in the blast that took his legs.

“I promised to make the best out of every moment I have left on this planet,” he said. “We are certain to face adversity in our lives. What matters is the attitude we bring to the table.”

He said a positive thought in the morning sets the tone for the entire day.

“Life is good, even when we think it is not.”